Before working on the next few variations, I like to help refine the student’s understanding of intonation. In Blog #5 we talked about the basic concepts of using the perfect intervals to check the intonation with the open strings. We also helped to organize the left hand in first position by checking the first and fourth fingers with the open strings, thus creating a clear “structure” for the left hand (for most people the tendency is for the first finger to be sharp and the fourth finger to be flat in first position). I usually like to give the students at least a week to sort this all out, so that they can play the theme with more stable intonation, especially regarding the first and fourth fingers. But then we need to address the middle fingers – the second and third fingers. For this I like to introduce the concept of what Casals called “Expressive Intonation”:

Now we will continue with the next several variations in Feuillard #32, dealing with Bow Distribution, staccato strokes, and a combination of those two concepts.

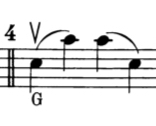

Variation #4:

The definition of Bow Distribution consists of two concepts: “how much bow we use, and which part of the bow we use”. In Variation #4 students will need to use the full bow (making sure that they really go all the way out to the tip), and then the upper half of the bow (using the lower part of the arm), and then the full bow (making sure that they go all the way to the frog), and then the lower part of the bow (using the upper part of the arm).

And they should be using Left/Right motion in order to further instill the concept of balance. However the choreography for the Left/Right motion is now a bit different: at the tip they should stay on the left side when using the lower arm and not rocking back and forth; then when they are using the upper arm in the lower part of the bow they should stay on the right side. We are training the coordination of the body for optimal ergonomic use, and this take some concentration until it becomes natural and easy.

I ask the students to write in their tempos for each variation at home, trying to figure out what the best speed should be for each one. Some variations “require” a slower tempo (e.g. those using the full bow); for other variations students will want to challenge themselves and find a faster tempo. Needless to say, there is a range of tempos that is possible – but as long as the student is in the “ballpark” with choosing a good tempo they are ok. One common element in finding the tempos is that we want a “core” sound, and they should use a good “block of sound”. It is more difficult to play with a low contact point and a good full sound – so that is what they should be looking for and practicing. If they choose a softer sound and a higher contact point I work with them to help change their “sound concept” to make the core sound their default for now. It usually takes a few lessons for the students to “get” what I am looking for in finding the tempos.

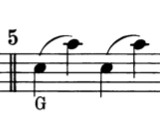

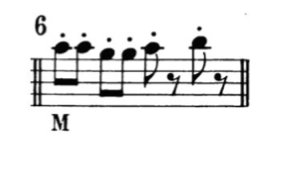

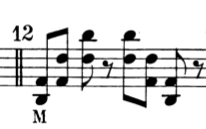

Variation #5:

This variation is written with dots over the notes. That could be interpreted as either staccato or spiccato. However I ask the students to play this variation only staccato for several reasons. First of all, they will be doing “off the string” strokes (spiccato) in their daily scale work (the first scale system that I have them do from lesson one onwards is a legato two octave system. In addition to the legato scale I also ask them to play the scale “off the string” using eight notes, triplets, 16th notes, sextuplets and octuplets at about 60 to the pulse. This lets them experiment with spiccato right away. Playing spiccato every day in this way gets them used to playing with this light stroke, and prepares them for being able to play a fast sautillé towards the end of No. 32). So, they are already getting some daily experience with spiccato.

Another reason for using staccato in Variations #5 and #6 is that they will absolutely need this stroke for Variation #7 (we can’t play spiccato at the tip, so it must be played staccato). And, playing with a good staccato with a good sound is in some ways more difficult than spiccato, because it is played closer to the bridge, with more weight. So we need to practice the more energetic and difficult stroke first. We practice what is hard, not what is easy!

In addition, Feuillard indicates “M” (middle of the bow) in Variation #5. For it to be played spiccato would require a very fast tempo, which is not important for a developing cellist at this point. So Variation #5 should be played with a staccato stroke, with equal attacks on the up and down bows at about 60 to the quarter note. The stroke is done in the middle of the bow with the lower arm and with the first finger “kissing” the stick onto the hairs and then releasing.

The rule that I mentioned here is “the lower the string the less bow speed is required; the higher the string the more bow speed”. That is why violinists have longer bows than bass players.

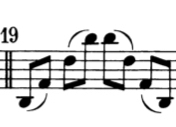

Variation #6:

The next concept that I need to share with the student (required for both Variations #5 and #6 as well as the upcoming detaché and many other strokes) is what I call “Catch and Float”. Every individual note has a beginning (the “Catch”) and then some sort of shape from the middle to the end of the note (“the Float”). There are innumerable possibilities for each of these, and all sorts of combinations of the two together. The “Catch” can have a hard accent, or a forte/piano sound, or a sforzando, or a delicate beginning, etc. And the “Float” can be lighter or heavier or with a crescendo, etc. The more colorful and creative one can be, the more interesting the playing. But we need to have total control of the “Catch” and the “Float” for every note.

The next concept that I need to share with the student (required for both Variations #5 and #6 as well as the upcoming detaché and many other strokes) is what I call “Catch and Float”. Every individual note has a beginning (the “Catch”) and then some sort of shape from the middle to the end of the note (“the Float”). There are innumerable possibilities for each of these, and all sorts of combinations of the two together. The “Catch” can have a hard accent, or a forte/piano sound, or a sforzando, or a delicate beginning, etc. And the “Float” can be lighter or heavier or with a crescendo, etc. The more colorful and creative one can be, the more interesting the playing. But we need to have total control of the “Catch” and the “Float” for every note.

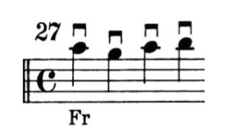

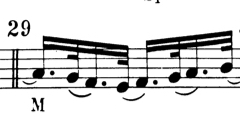

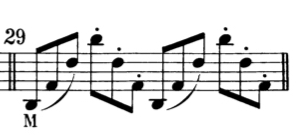

Variation #7:

This variation deals with a combination of bow distribution and staccato (based on variations #4 and #5). By combining these two concepts the students are working on coordination. This is a good example of how the Feuillard builds technique in a logical and sequential manner. We learn one thing, then we learn another, and then we combine them.

For the left/right motion we need to learn a new choreography: staying on the left side when playing at the tip, and on the right side when at the frog. We will also have to change the contact point from high (for the quarter note, because of the fast bow speed) to low (for the staccato notes) for the same volume. Sometimes I need to remind the students to continue to use vibrato (that is what I was doing in this video shaking my left hand while she was playing) – this is important for the sound, but also because it involves coordinating the left/right motion with the completely different motion of the vibrato. It is like tapping our head and rubbing our stomachs!

As we work on the various bowing issues, we also always need to remind ourselves about basic fundamentals, such as our sitting position or the fact that we need to prevent ourselves from crunching down. And we need to pay attention to things like the bow angle, the Front and Back of the hand, the elbow arc, etc. In short, we need to “multi-task”. I sometimes tell the students that this is “good multi-tasking” – playing, while listening to our colleagues, while watching the conductor, etc. As opposed to “bad multi-tasking” such as driving and texting!

Next week’s blog will work with variations #8 – #13, dealing with dotted rhythms, more staccato strokes, and detaché strokes.

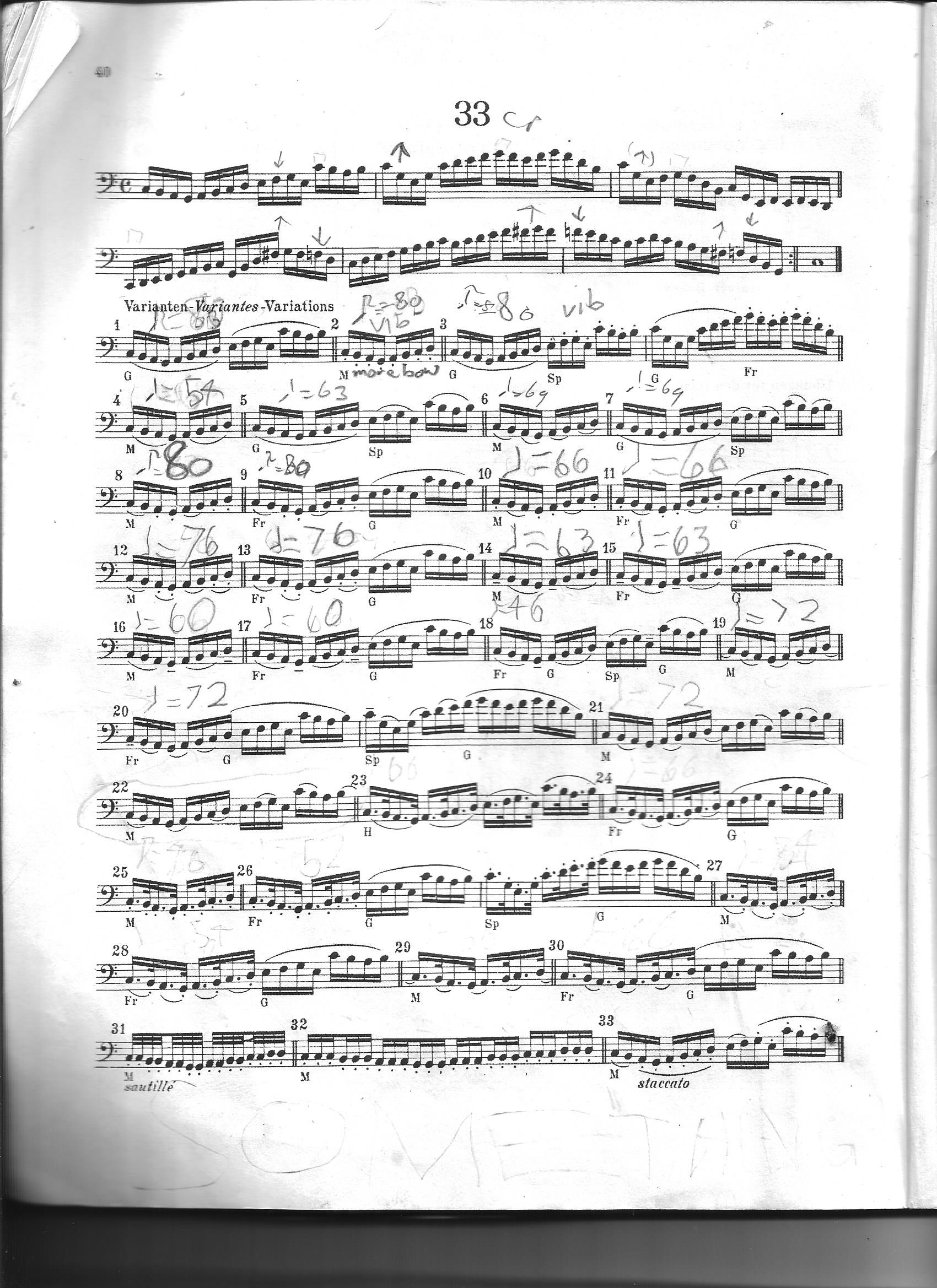

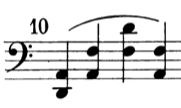

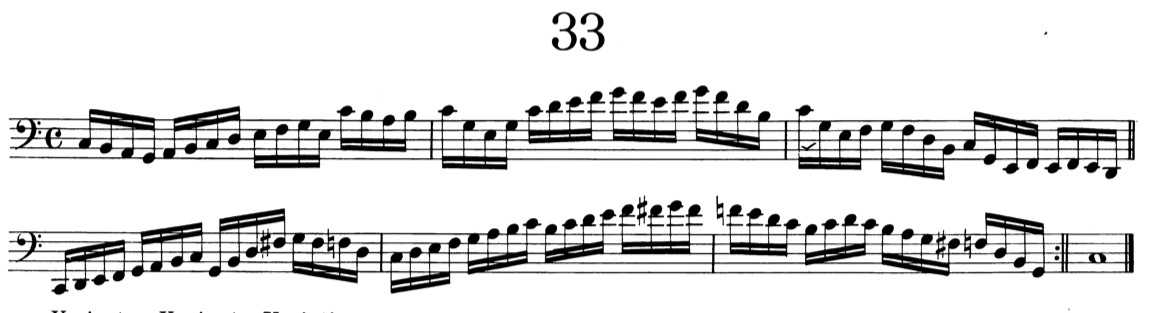

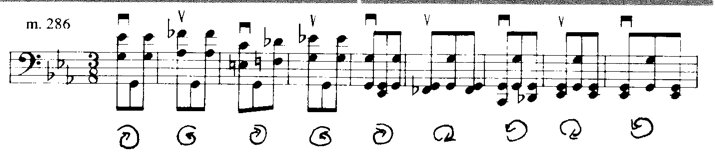

In the Gigue from the Third Suite, the motion involved is a figure eight, which then reverses direction after four measures. The arm is on the G-D double stop level, and the wrist does the string crossings:

In the Gigue from the Third Suite, the motion involved is a figure eight, which then reverses direction after four measures. The arm is on the G-D double stop level, and the wrist does the string crossings:

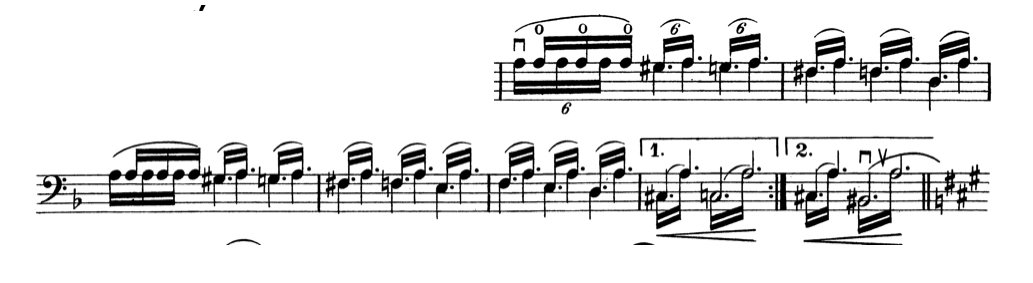

These are just a few examples from the literature. Every passage involving string crossings is different, but it is helpful to analyze the underlying bowing figures involved and to practice them slowly.

These are just a few examples from the literature. Every passage involving string crossings is different, but it is helpful to analyze the underlying bowing figures involved and to practice them slowly.