Blog 1 – Introduction

I started playing the cello seriously in 1971 when I was 22 years old. I had played somewhat earlier, but had very few lessons and was certainly not even considering music as a career. When I went to college I thought I was going to be a doctor, and I majored in anthropology and linguistics. It was only when I finally recognized that I really didn’t want to pursue those career goals that I decided to “try” this music thing. When I went to Freiburg, I played for cellist Marçal Cervera, who ultimately became my teacher. He heard me play, and told me that there was “no way” that I could be accepted into the Conservatory. I just didn’t have the technique or background to make that possible. But he suggested that I study with a student of his, and that I should come back after a year and he would see what progress I had made. We essentially started from scratch – literally! Open strings, basic technique, tone production – and Feuillard. We started with the No. 32 bowing exercises – working on creating a “sound concept”, understanding how the body works most efficiently, and learning how to be relaxed while playing. I came back after a year and did the Aufnahmeprüfung (Entrance Exam) for the Conservatory, and – lo and behold – I was accepted. I then studied with Maestro Cervera for 4 years and on graduation became principal cellist of the Orquesta de Las Palmas in Spain. The rest is “history”…

Fast forward almost 50 years from my Freiburg days, and I am thankful that I was given such a solid basic foundation for the right hand, and a thorough understanding of bow usage. The bow is where the artistry lives in playing a stringed instrument. As an artist one must be able to control every aspect of the bow as we work towards our artistic goals. But we must first master our craft on the way to becoming artists. We must know all the elements for controlling the bow to produce the rainbow of colors that we need in music. We need to be able to get a good sound from all parts of the bow, and to play with accurate rhythm. We need to know about bow distribution, how to play legato, detaché, spicatto, sautillé and all the other strokes. And we need to know how to shape phrases. We need to be able to sing with the bow, and also to speak with it. In short we need to be able to control the bow, rather than having the bow control us. If the bow is a horse, and we are the rider then we need to control the horse, not vice versa.

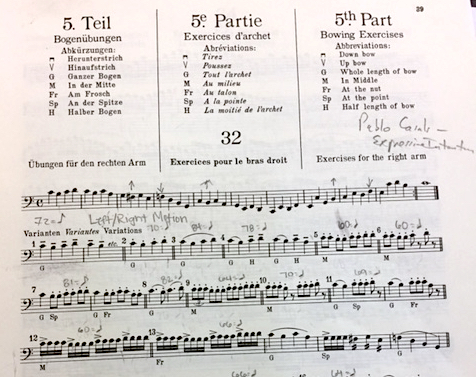

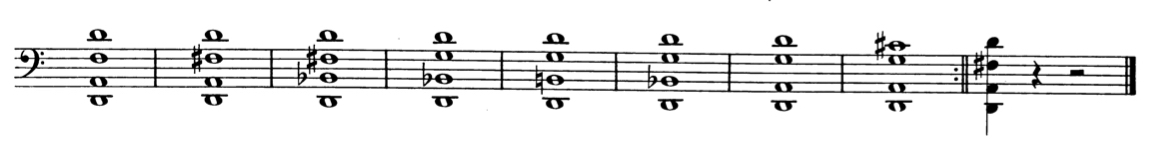

I have been teaching the cello for about 45 years, using the Feuillard Daily Exercises in my private applied lessons since the very beginning of my teaching. I use almost all parts of the book, in addition to a healthy diet of etudes (Dotzauer, Lee, Duport, Popper, Franchomme, Piatti, Servais and others). For the left hand I use the book’s 2 octave and 4 octave scales and arpeggios for basic left hand organization, as well as the thumb position scales and arpeggios (No. 26-27). I also use the shifting exercises (No.16), the position-changing exercises (No. #3-7), as well as the trill exercises, and virtually all the other sections as warm-up exercises for my students and for myself. The advantage of the Feuilliard is that it has all of these exercises in one book, and it is brilliantly organized.

This blog will focus on how I teach bow technique using the Feuillard Daily Exercises No. 32-36. It is an example of what I call the Sequential Method of teaching, which I will discuss further in Blog 2 of this series.

For this blog I am assuming that a student comes to me having already played for a few years as a beginner or intermediate cellist. He/she may be a middle school or high school student who has started in a public school or Suzuki environment, perhaps with some private lessons. He/she enjoys playing and wants to be more serious about music and become a better cellist. I expect these students will practice at least 1 1/2 hours a day (I always have a sit-down commitment discussion with the parents and the student prior to the first lesson).

I also use these bowing exercises with incoming college students who may already play on an advanced level, but have little understanding of what they are actually doing. Sometimes they have “holes” in their technique or need to move a step backwards in order to rebuild the foundations of their technical understanding. And I use these Feuillard exercises with my graduate students (performance or pedagogy) who will be teaching students themselves. Virtually all musicians nowadays need to be passing their skills on to the next generation. In addition, I use these exercises as my own daily warm-up!

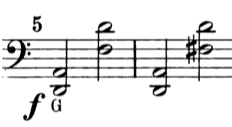

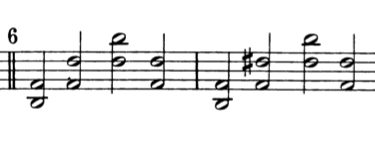

After showing a student the basic elements of the bow (essential sound production, parts of the arm, the Three Principles of Sound Production, etc) I start to explain how the Feuillard exercises work. They consist of a theme and then a page of variations that focus on various elements of bow technique. There are five pages of variations, each with a different theme:

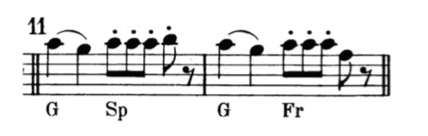

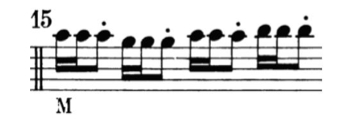

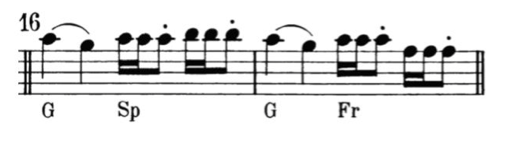

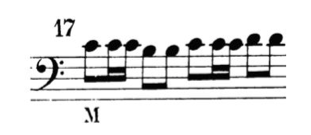

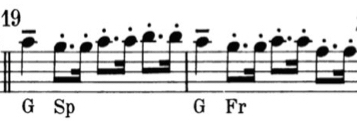

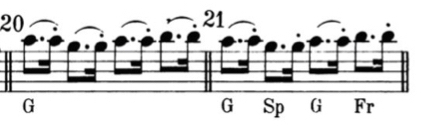

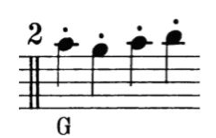

- No. 32: The theme of Feuillard No. 32 is all in first position. It is perfect for the student to solidify the basic technical issues of the bow. Each variation should be polished like a gem and “perfected” with good sound and a “mastery” of the fundamental bow technique. Terms should be clearly understood, including the difference between spiccato and staccato, and the importance of a well-executed detaché or legato.

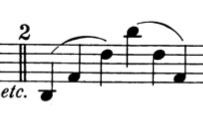

- No. 33: The scalar theme of Feuillard No.33 adds some complexity by going up to fourth position. This means that the student has to be aware of the contact point going closer to the bridge as the string length is shortened to achieve the same sound as in first position. The variations in No. 33 provide opportunities to work on playing with more notes in a bow (son filé) while keeping the sound full and rich throughout the bow and on all the strings. It also builds on various techniques from No.32 (dotted rhythms, sautillé, up-bow staccato), as well as issues of coordination and ease of playing.

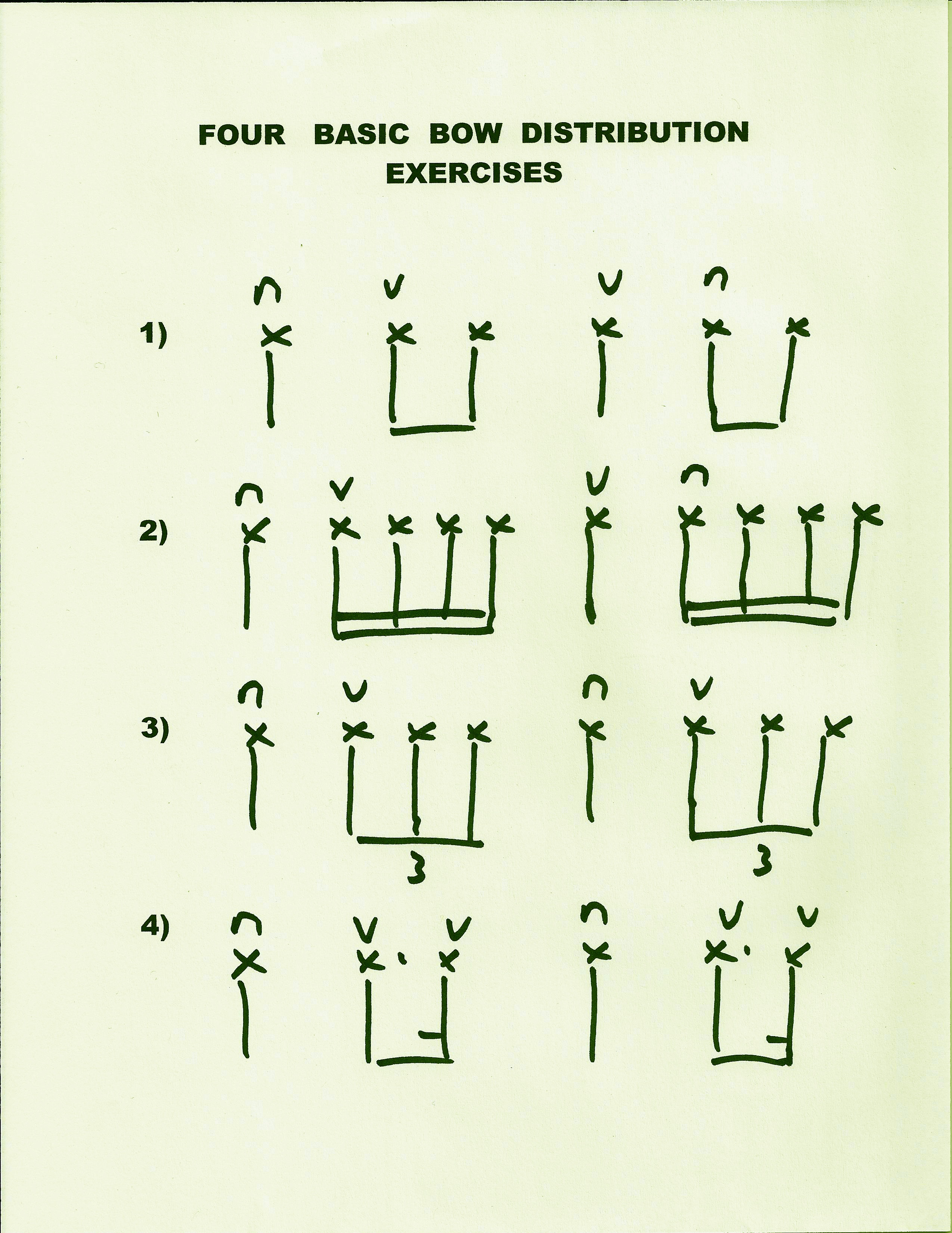

- No. 34: The next three pages (Feuillard No. 34-36) all deal with string crossings as the main topic, with No. 34 using 2 strings, No. 35 using 3 strings, and No. 36 using 4 strings. Cellists (and other string players) must understand how string crossings work. If players do not use the arm in an ergonomically correct manner, then string crossings can become a major source of tendonitis. Besides understanding how the various joints of the arm move (e.g. ball and socket vs. hinge joints) the string player must understand that all of the complicated string crossings boil down to four basic bowing figures: the Arc, Circle, Figure 8 and Wave.

- No. 35: I use Feuillard No. 35 to explore the use of a “twist” motion: the pivoting of the body core around the pelvis to assist playing on the upper versus the lower strings.

- No. 36: Feuillard No. 36 deals with four strings – chords, twist motion, and a summation of all the techniques from the first four pages.

It usually takes about 2-3 years to get through all five pages, depending on the student. But by the time they finish, they have a good understanding of the bow and how the arm works. All along they are using these techniques in etudes and repertoire, and other exercise books such as Sevcik.

In this series of Blogs, I intend to demonstrate how I teach French bow technique using the logical, sequential material in Feuillard. These Blogs essentially comprise a syllabus for teaching the Feuillard – showing the pedagogical intent of each variation.

For these Blogs I have asked several of my pre-college students if I could video-tape their lessons and use clips of my teaching and their playing in the lessons to demonstrate the process. These are not “staged” – they are taken directly from actual lessons. I would like to thank the students, who are helping to make this Blog possible in this way. The students are:

Caroline – to be featured in the videos of No. 32

Iestyn – to be featured in the videos of No. 33

Tristan – to be featured in the videos of No. 34

Zach – to be featured in the videos of No. 35

George – to be featured in the videos of No. 36

This series of Blogs is intended for cello teachers who wish to become more organized in the way that they teach bow technique. It is also intended for cellists young and old who want to explore and improve their own right hand technique, beginning with fundamentals and working through sophisticated uses of the bow.

These Blogs originally came out every Monday on CelloBello over a period of a nine months. In the next Blog I will discuss the underlying pedagogical and philosophical concept of the Sequential Method, which forms the basis of my way of teaching.

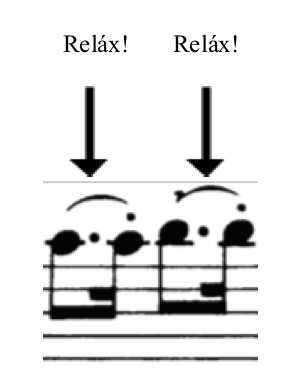

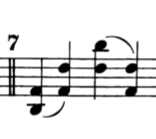

String players are notoriously bad at playing dotted rhythms. It may be somewhat easier for pianists and wind players to play this rhythm accurately because they are not inclined to sustain the ends of the notes. But we string players need to be able to surmount the challenge and be accurate in our playing of the rhythm.

String players are notoriously bad at playing dotted rhythms. It may be somewhat easier for pianists and wind players to play this rhythm accurately because they are not inclined to sustain the ends of the notes. But we string players need to be able to surmount the challenge and be accurate in our playing of the rhythm.

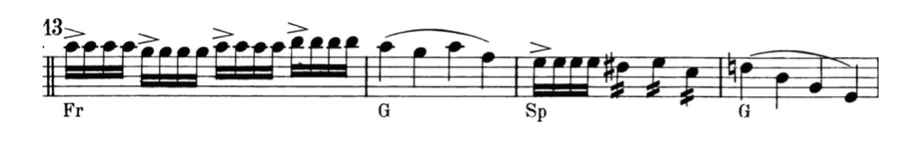

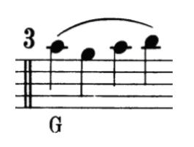

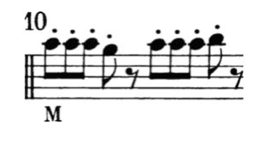

These variations work on the staccato stroke again, and are a good way to check up on whether a student remembers some of the earlier concepts that were taught, including using the right part of the bow and arm, the contact point for staccato, and “catch and float”. Number 10 is also interesting in that the rhythm switches between triplets and duples.

These variations work on the staccato stroke again, and are a good way to check up on whether a student remembers some of the earlier concepts that were taught, including using the right part of the bow and arm, the contact point for staccato, and “catch and float”. Number 10 is also interesting in that the rhythm switches between triplets and duples.